Last summer, on a day trip of sketching in the countryside of Central Italy, north of Rome, I started my day in the peaceful little town of Corchiano. Like so many of the ancient towns in the area, Corchiano hangs on a peninsula cliff. I was determined to draw the town from below, and found a path that lead down and around to below the cliff on which the town perched. Scampering along a narrow path I came to a gate with a big sign nailed to it that stopped me. And stumped me.

The sign said, in big, bold, red letters, "RICHIUDERE IL CANCELLO.” Above that, in slightly smaller letters, it said, "Attentione Animale in Liberta" along with a picture of the sweetest donkey face in the world. Along the top of the sign were all the insignias of an official decree. This sign was telling me something important and saying it officially. But what? As someone who speaks little Italian, I was puzzled, and a bit alarmed. To me, it seemed that the sign was warning me not to go beyond the gate because there is a donkey up ahead. So, heeding the warning, I went all the way back up to town, and then around and down along the other side of the peninsular to find an alternate view. But alas, an identical sign was hung on a matching gate over there, too.

The question that formed in this stubborn artist's head (stubborn, in that I was determined to draw from below this town), was, "Should I be afraid of donkeys?" After some thought, including some imagined violent scenarios—mostly involving kicking—I "bravely"passed through the gate, into the wooded area ahead, around and about many donkey droppings.

Now, mind you, these silly situations are not uncommon for me. I often suffer from dilemmas totally of my own making. Lost in Translation would be a very suitable title for most of my Italian travel stories.

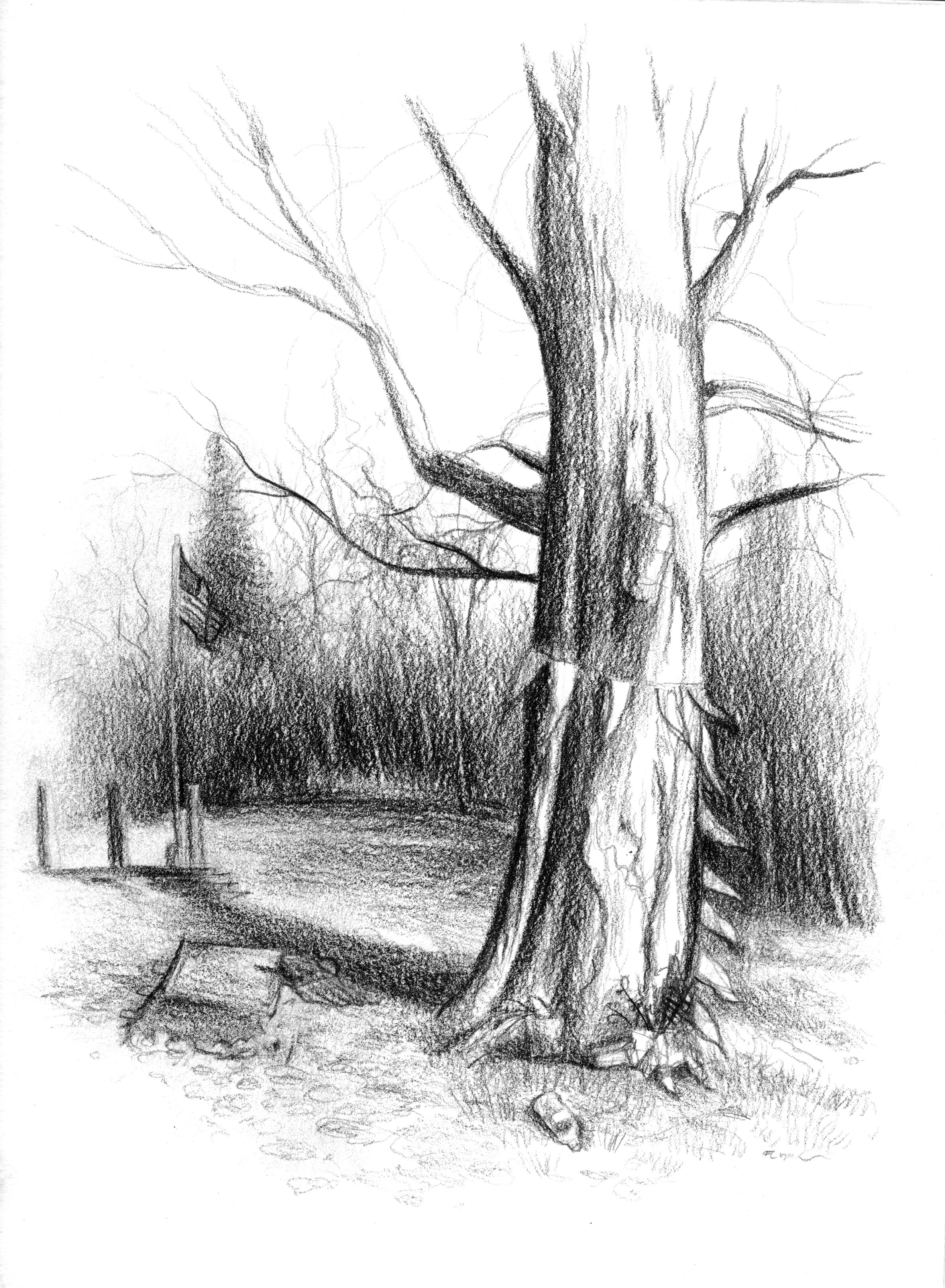

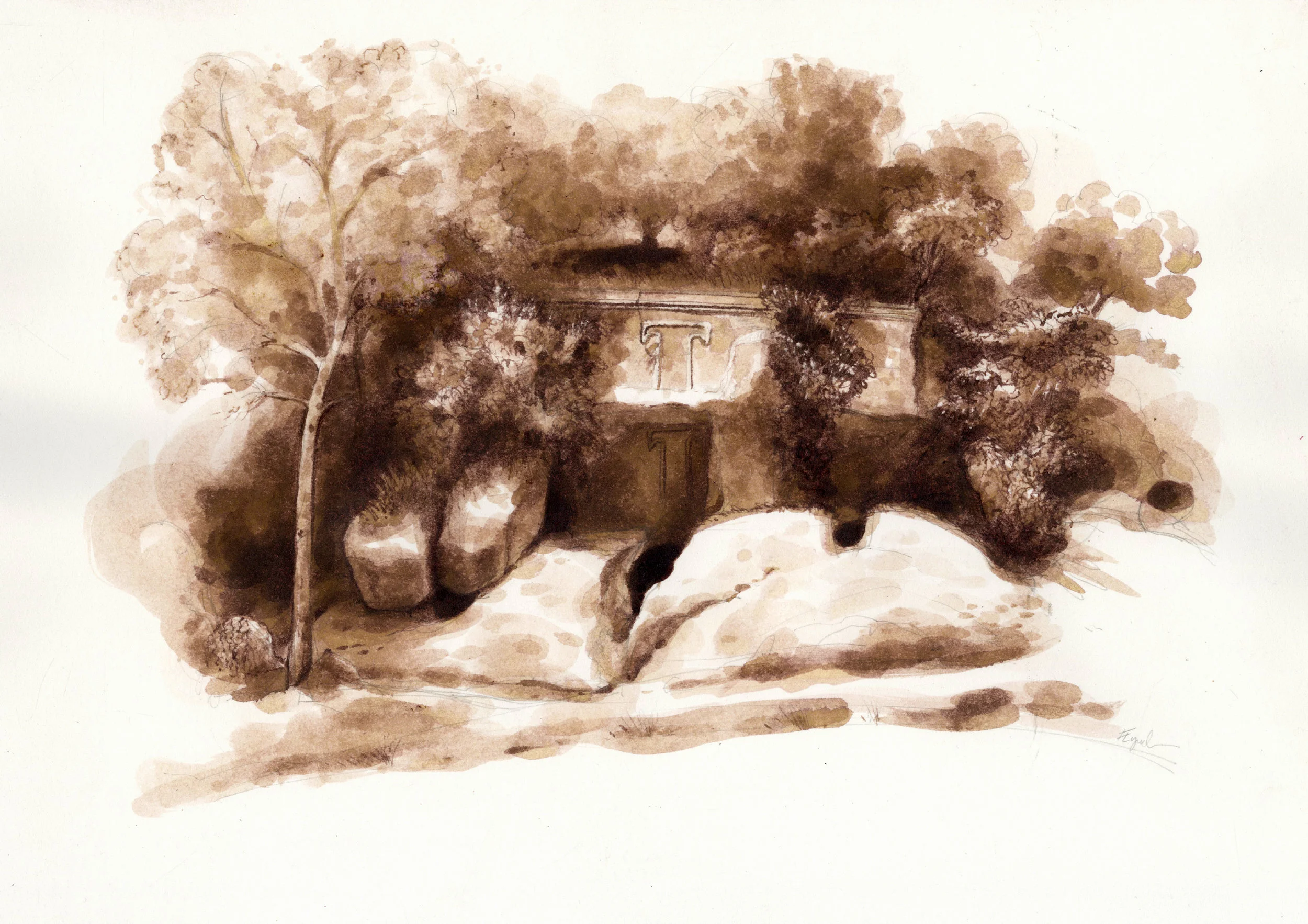

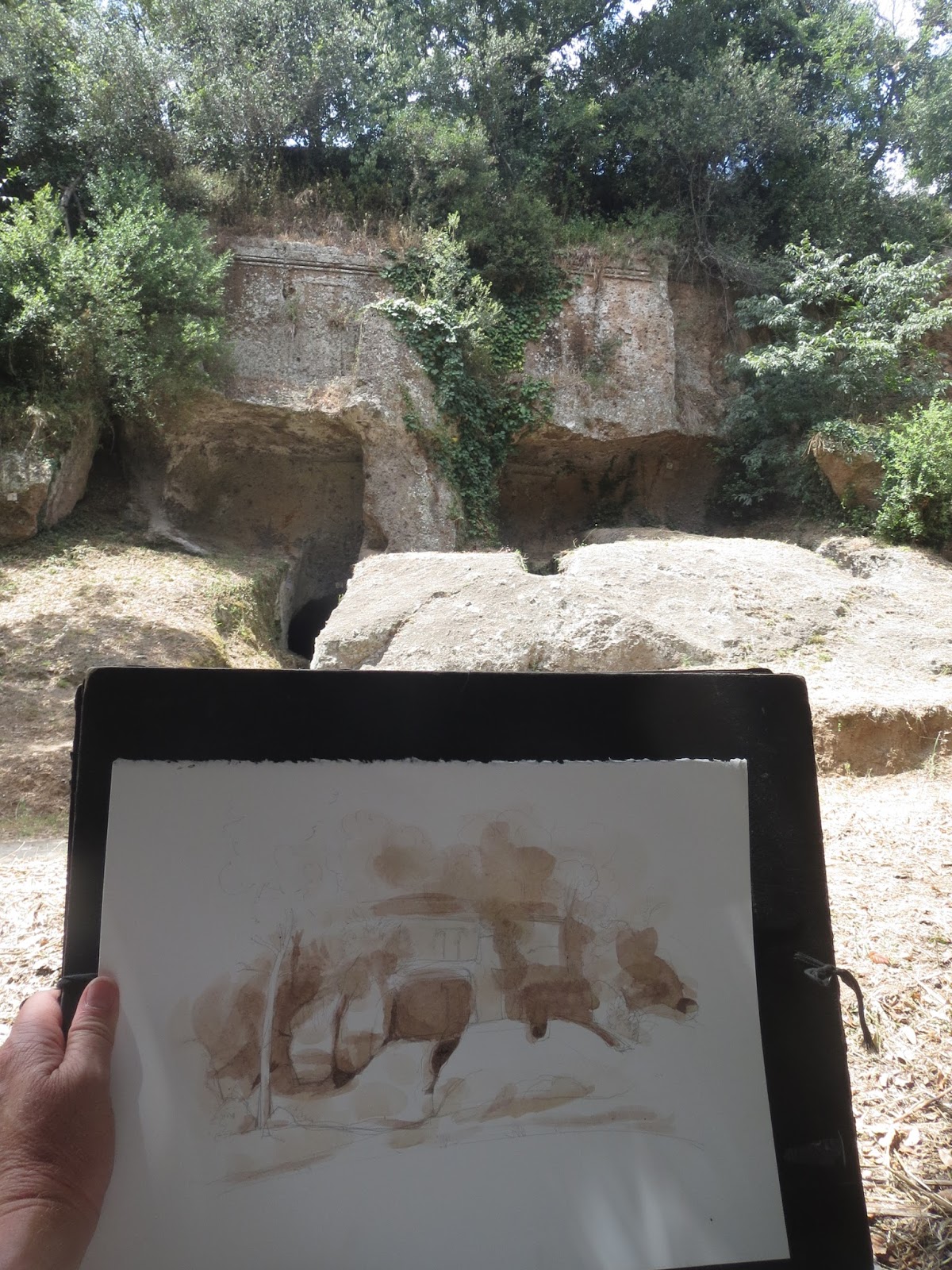

Finally finding the dramatic view I craved, I sat and sketched for 90 minutes, all the while listening carefully and looking over my shoulder often—so as to not be suddenly attacked by a violent donkey.

After packing up, I walked further along the path to what looked like a little bridge which offered one more glimpse of the striking view. Turning the corner, I came face to face with not one, but two donkeys! I jumped, made what I'm sure was a gutteral squealing sound and backed away from the animals, as they looked at me sleepily, barely blinking an eye.

Turning on my heels, I made a hasty retreat. Following the path back to town, I looked over my shoulder and saw that they were following me! Actually, moseying, would be a be a better word. Just as I noticed they were coming, they stopped for a bite of grass. I hustled out of the gate, and found my wife in a local cafe, where I told her the whole stupid story. I knew it was ridiculous, but she knew I was ridiculous. Later, I learned the sign simply asked that I remember to close the gate. You could say it was a story about two donkeys and an ass.